Let’s talk about the de Acosta sisters. Never heard of them? Well these were very busy ladies in the early to mid 20th century, and there is a lot to discuss, so I’m just going to jump right in with how Gail Collins, in her book, American Women, introduces one of them:

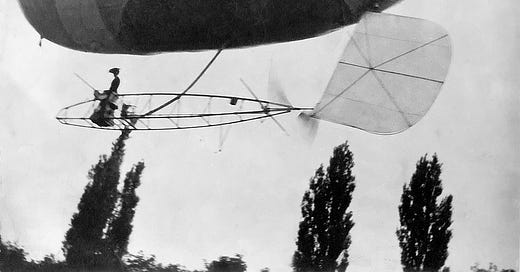

Early aviation was another one of those enterprises that was so disorganized it was easy for women to get involved. In the beginning, anybody who had enough nerve could take to the sky. In 1903, Aida de Acosta, a young Cuban American, was vacationing with her mother when she got a look at some dirigibles. After three lessons of flight instruction, she became the first woman to fly a powered aircraft alone - months before the Wright brothers took off at Kitty Hawk.1

The idea that early flight ‘so disorganized that it was easy to get involved in’, is a little mind-boggling, but all power to Aida for her bravery and opportunism. So who was she, and what about her sisters?

Aida de Acosta was the fourth of eight children born to a Spanish mother and Cuban father. The story goes that their mother came to America from Spain to recover, through the courts, a fortune stolen from her by a wicked uncle. Their father was a Cuban national and liberation fighter who escaped a firing squad before settling in America and becoming a highly successful executive in the booming steamship business. Whatever the truth of these tales, by the time their children came along, the family was wealthy, established in New York society, and mixing with Roosevelts and Vanderbilts. Certainly there was money enough for trips to Europe like the one where Aida flew the dirigible, and a lot of care for reputations, at least according to this newspaper article, which declares Aida’s mother was entirely horrified by her daughter’s escapade and insisted she tell no one a word about it.

Presumably, Aida’s main task at the time ought to have been making a good match, something her older sister Rita had achieved in 1895 when she married William E. Stokes. Over 1000 people attended this society wedding but the marriage did not go well. Five years later, Rita de Acosta won what was at that time the largest divorce settlement in history. Before Aida took flight in 1903, Rita had made another excellent match, at least in financial terms, and was now Rita Lydig, a fabulously wealthy socialite and accredited beauty, with a passion for fashion.

An art patron and ‘shoe queen’2, Rita was credited with being the first woman to wear a backless dress, but being fashionable didn’t mean she was empty-headed. She was a member of the Colony Club, the first New York City social club for women, she supported the Women’s Trade Union League during the shirtwaist strike of 1909, and rallied for suffrage in 1912. She also knew a lot of highly talented people. Here’s Rita’s much younger sister, Mercedes, describing a visit to Paris:

When I was only ten, Rita took me to see many great artists in Paris. She treated me like a grown up and used to introduce me then as her “canary.” Later on she always referred to herself and me as “The Sisters Karamazov.” I met Rodin, Bourdelle, Henry Bergson, Brieux, Anatole France, Boldini, Yvette Guilbert, D’Annunzio, Edith Wharton, Helleu, Sarah Bernhardt, Jacques Copeau and many others.3

Mercedes, 17 years younger than Rita, idolized her older sister:

Rita was my first conscious glimpse of beauty and all through my life she symbolized beauty to me… I can truly say that I have known a number of extraordinary and beautiful women the world over, but Rita considered objectively and without any prejudice in her favor, seemed to me to be more striking, more unfailing in perfect grace and beauty than any other woman. And with these physical characteristics she combined a remarkably magnetic personality.4

It is true we were sisters, but by choice, foremost we were friends, and after nearly a lifetime of evaluating her, I think I can say without prejudice that I have never met any other woman of her quality.5

Rita also really, really did love shoes. Here’s how Mercedes De Acosta’s biographer, Robert A. Schanke, described Rita’s shoe collection:

She owned 150 pairs of shoes, some never worn, each custom-made by Pietro Yantorny, constructed of silk, satin, velvet, and laces, and stored in Russian leather cases – twelve pairs to a case. One of the features of the Metropolitan Museum’s 1948 ‘Turn of the Century’ exhibit was a pair of Rita’s two-inch-wide, white, pencil-pointed satin shoes trimmed with heavily appliqued Venetian lace.6

If, like me, you are impressed by these shoes, but have not previously heard of Yantorny, here is Mercedes’ entertaining description of this master shoemaker at work:

He was the shoe curator of the Cluny Museum in Paris and there was nothing he didn’t know about shoes of every period. By birth he was an East Indian but he lived most of his life in France, following his own way of life which was very ascetic. He was a vegetarian and seldom ate more than one meal a day. He went into designing and making shoes because he had a passion for them. He had his own ideas about making them and he didn’t make them for everyone. If Yantorny decided to make you a pair he would make a cast of your feet in plaster, at the same time measuring every inch of both feet. He would observe them walking barefoot to watch just where the weight was placed, and he would feel them, holding and balancing them in his hands. He would ask you to contract them and make them limp and then put you through a series of toe-spreadings. If he finally decided to make you your shoes, you could count on the first pair being delivered in about two years.7

Rita’s home in New York was designed by Stanford White at 38 East Fifty-Second St. It’s not there any more, but Rita helpfully (likely because of looming money troubles) produced a catalogue of her home and art collection. You can examine the full catalogue online, but here are two photographs from the publication that give you a good idea of how Rita lived.

Rita had her share of fortune and misfortune. Two failed marriages, one son who lived largely with his father, struggles with her health, and financial mismanagement meant that when she died in October 1929, Rita had long since had to sell off her art collection and was living in very reduced circumstances in the Gotham Hotel. One of her latter attempts to recover from her financial troubles was writing a book, Tragic Mansions, a semi-autobiographical novel and critique on New York society.

Mercedes, in her autobiography, Here Lies the Heart, explains that Rita had suffered…

…from an accident she had been in many years before while driving in a Hempstead cart in Westbury, Long Island, with Aida. The horse Rita was driving ran away and fell against an embankment, at the same time kicking the dashboard to pieces so that they both fell out of the cart and landed on the ground beneath his feet.

Aida nearly died as a result of this accident. She had to have several major operations and this was the cause many years later of the glaucoma which lost her the total sight of one eye and the partial sight of the other. Paradoxically enough, had she not lost her own sight she would never have become interested in the blind and been interested in organizing the Eye Bank as she later did.

At the time of the accident Rita appeared only slightly injured, but it was just this injury that created internal complications which years later, in 1929, caused her death.

Eye Bank? Aida? Yes.

Still in operation today, the Eye-Bank of New York’s website has a page about their history where they credit Mrs. Aida de Acosta Breckinridge as ‘a public relations powerhouse’. The organization, founded in 1944, led the field in cornea transplants. Aida brought in five former first ladies, including Eleanor Roosevelt, to support the cause, as well as former president Hoover, Ethel Barrymore, and Thomas Watson, the founder of IBM.

There can be no questioning it - the de Acosta sisters were a well-connected bunch.

Which brings me to youngest sister, Mercedes, a screenwriter, novelist and poet… and, the lover of some very, very famous women.

It’s reading about Mercedes de Acosta that has made me take SO long on this post. I’m very keen to do her justice and not just jump on the facts about her love life. To this end, I’ve read Mercedes 1960 biography, Here Lies the Heart, which came out eight years before she died, aged 76.

The whole family dynamic is complex. The de Acosta father killed himself by jumping off a cliff in the Adirondacks in 1907. Older brother Hennie gassed himself due to depression in 1911, and it was nineteen-year-old Mercedes who discovered his body. She describes a childhood of privilege, but also inner melancholy, deep feeling, and insecurity, despite lifelong close bonds with her mother and her sisters, particularly Rita. There’s a sense, reading her words, of a woman before her time. This is a woman who gave up smoking because Ghandi had declared smoking hampered a person’s spirituality. Who believed she had a psychic sixth sense and experienced premonitions. Who read Buddhist philosophy and traveled to India. Who walked out on a scriptwriting job in Hollywood because she refused to write an historically inaccurate sex scene in a movie about Rasputin. Who called up Marlene Deitrich and told her if she kept sending flowers she would throw her in her own pool. Mercedes de Acosta was famous for walking the streets of New York in mannish pants, wearing pointed shoes trimmed with buckles, and a tricorn hat. In the roaring 1920s, she knew everyone who was anyone and became a successful poet and novelist.

But when Mercedes de Acosta is remembered now, it’s not for any of those reasons. As Hugo Vickers puts it in his 1994 book, Loving Garbo, The Story of Greta Garbo, Cecil Beaton, and Mercedes de Acosta:

Mercedes wrote novels, plays, and film scripts, and her poetry was published, although no one reads it now.8

(Hmm. Well, there was also her autobiography which was well-received at the time, and published novels as well as several books of poetry, but who is counting? Not Hugo Vickers.)

Instead, it is her love life that makes her a continuing person of interest, and an important figure in queer history9, partly, yes, because of the famous women she had relationships with, but also because of her own life and the way she chose to live it. In her autobiography, it’s clear she had very close, intense, relationships with a number of women, notwithstanding a fifteen year marriage to the artist Abram Poole, but Mercedes doesn’t spell things out. How could she? It was 1960. And so, while the biography allegedly infuriated Greta Garbo (Marlene Dietrich, on the other hand, read drafts of the manuscript and was very supportive) there is much left unclear/unsaid. She had, however, towards the end of her life, sold her papers, letters and the manuscripts for Here Lies the Heart to the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia, and it’s in these papers, and in the diaries of photographer and artist Cecil Beaton that we learn a lot more. It’s Cecil Beaton who called her “that furious lesbian”, and “one of the most rebellious and brazen of lesbians.” in his unpublished diaries.10 His view of Mercedes, perhaps not un-tinted by his own affair with Greta Garbo, is not the kindest. The papers in the Rosenbach, including Mercedes’ draft manuscript for Here Lies the Heart, offer more revealing insights to Mercedes’ life, two of which really stuck out to me.

The first is Mercedes detailing her childhood belief that she was a boy. In these days when transgender issues are constantly in the news, it’s thought-provoking - whatever your views may be - to read about a person, born in 1892, growing up believing she was a boy. She describes a confrontation that took place when she was seven, when a group of boys she was playing with refused to believe she was a boy and exposed themselves to her, demanding she do the same a prove she wasn’t a girl. Of course she could not, and was traumatized by the whole event, not long after telling a nun at her convent school:

I am not a boy and I am not a girl, or maybe I am both, I don’t know. And because I don’t know, I will never fit in anywhere and be lonely all my life.11

And then there’s her application to become editor of Victory magazine in 1941, a job within the Office of War Information. In her published biography, Mercedes recalls “I applied for the job, and after making out dozens of governmental papers, I got it.” Biographer Robert A. Schanke found in an earlier draft describing this episode, where Mercedes details undergoing an FBI interview as part of the application process. She wrote:

He then said, with rather an uneasy air, ‘It seems to me looking through these pages that you have a great many men friends who are not on the level sexually.’ I thought this a quaint and original way of describing homosexuality. I laughed. He continued, ‘This is not a laughing matter, and now that we are on the subject, how would you describe yourself, speaking, of course, purely sexually?’ He blew his nose again and looked embarrassed. I was about to get angry when I remembered Rita’s instructions to me when I was a child: ‘whenever in a difficult situation, handle it with humor.’ I thought quickly. Quite indifferently, I said, ‘Oh. I am ambidextrous and androgynous. A sort of combination of both.’ He leaned across the table and shouted, ‘You are what?’ I repeated what I had said. He turned to his secretary and asked, ‘Can you spell those words?’ She said she could not and did not even know what they meant. ‘Spell them for her,’ he commanded. ‘I’m afraid not,’ I said. “I am not here to give the government spelling lessons.”12

Ha! She pulled no punches, and yes, she still got the job.

Overall, I found Here Lies the Heart to be an odd mix of name dropping and jet-setting, punctuated by some quite profound passages on the lives of women, creativity and purpose. Perhaps, had Mercedes been writing at a different time, her autobiography would be more impactful and reflect more the person we see in the passage above, living up to her claim in the published version that “As long as I feel ‘right’ within myself, so called ‘society’s’ opinion never influences me for a second. Even in my youngest days I already knew how easily opinion could be swung and altered.”13 But then I’m not a bold lesbian woman (furious, rebellious, or brazen) living a complex life in a time of repression, so who am I to wish for her to publish anything other than the words she chose?

Mercedes own words, in fact, feel like a good place to end this. Here’s one of her poems, from Archways of Life (1921), presumed to be written about her then presumed lover, the actress Eva Le Gallienne. I think it speaks for itself:

Today is your birthday.

Many people will come to you with offerings,

While I,

Who seemingly know you so slightly,

Yet who truly know you so well,

Must stand aside with empty hands,

If love could make this day perfect,

My love would weave for you

A web enmeshed with all your desires.

On your pathway

I would fling stars for pebbles

And tear down the moon

So that you might wear

The radiance of its silver

In your hair.

But instead –

I stand outside like a wall

And quite powerless

I send no gift at all.14

America’s Women, 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines by Gail Collins, 2007

Here Lies the Heart by Mercedes de Acosta, 1960

ibid

ibid

That Furious Lesbian, The Story of Mercedes de Acosta by Robert A. Schanke, 2004

Here Lies the Heart by Mercedes de Acosta, 1960

Loving Garbo, The Story of Greta Garbo, Cecil Beaton, and Mercedes de Acosta, by Hugo Vickers, 1994

Ooh. I just ordered a copy of this book: A Short History of Queer Women by Kirsty Loehr

Cecil Beaton published 6 volumes of diaries and a couple of other titles of interest. The Glass of Fashion, 1954, includes a chapter devoted to Rita de Acosta Lydig, and The Book of Beauty, 1933, which is full of society sisters I need to follow up on, including his own sisters, Nancy & Baba.

Loving Garbo, The Story of Greta Garbo, Cecil Beaton, and Mercedes de Acosta, by Hugo Vickers, 1994

That Furious Lesbian, The Story of Mercedes de Acosta by Robert A. Schanke, 2004

Here Lies the Heart by Mercedes de Acosta, 1960

That Furious Lesbian, The Story of Mercedes de Acosta by Robert A. Schanke, 2004

This was exactly what I needed to read today on my birthday❤️ thanks for introducing me to this interesting woman I can’t wait to read more of her work.

Sad to say that even in my years dealing with them in the latter half of the last century our security guardians still have little imagination beyond their ability to conjour endless fears and threats out of gossamer