Ok, this post is not for the faint of heart. Reading up on the Papin Sisters, a pair of French murderer sisters, has not been the most pleasant piece of research I’ve ever done. Let’s hit the grisly highlights first and then get on to some thoughts about why gruesome crime, violence and incest are somehow way more acceptable in fiction than in fact.

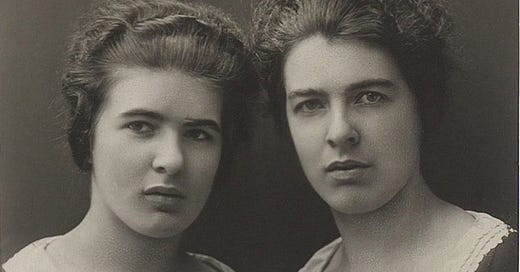

The basic story of Christine and Léa Papin goes like this. The sisters were born in 1904 and 1911 respectively, making Christine 28 and Léa 21 when they brutally murdered their employer, Mme. Lancelin, and her daughter Genevieve, on February 2nd, 1933. No surprise, the Papin sisters had a troubled background. Their mother, described as ‘not maternal’, had accused their father of molesting the girls’ older sister Emilia, and the younger girls largely grew up living with relatives or in an orphanage. While Emilia was allowed to join a convent, their mother insisted Christine worked as a maid, and in 1924, she and Léa started working together. In 1927, they entered the employment of a lawyer, M. René Lancelin, working as live-in staff in his spacious home in Le Mans, with their own room in the attic. On the evening the crime took place, M. Lancelin was out playing bridge. When his wife and younger daughter returned home before him, it appears an argument broke out between the two maids and their employer over a blown fuse caused by a faulty iron. Here (and be prepared, this is gruesome) is what Christine Papin said then took place.

Seeing that Mme. Lancelin was going to rush at me, I flung myself in her face and tore her eyes out with my fingers. When I say that I flung myself at Mme. Lancelin, that’s wrong. I flung myself at Mlle. Genevieve Lancelin and tore out her eyes. While this was going on, my sister Lea leapt at Mme. Lancelin and tore her eyes out. When we’d done that, they lay or squatted down on the spot; then I hurried down to get a hammer and a kitchen knife. With these two instruments my sister and I set about our two mistresses. We hit them over their heads with the hammer and slashed their bodies and legs with the knife. We also hit them with a little pewter jug which was on a little table on the landing, and we changed instruments several times — I handed the hammer to my sister and she handed me the knife. We did the same thing with the pewter jug. The victims began howling, but I don’t remember their actually saying anything.1

Ok, so the frenzy I can get. The knife. The hammer. And the pewter jug is exactly the kind of little detail that would be a must in a fictional account of this. But the eye gouging? Wow. Impossible not to think about Oedipus, but this is something else again. Two sisters each going straight for the eyes? It’s totally chilling. (There is a grainy crime scene photo available but I don’t feel like having in it this post so clicking on the hyperlink is optional.) But back to the story. When M. Lancelin returned home he found the front door bolted. After knocking and waiting for about 2 hours he went to the police. When the police gained entry they found the brutally battered bodies of two women on the landing with their eyes lying nearby on the stair carpet. Christine and Léa Papin were upstairs, locked in their room. When the lock was broken, the sisters were found lying side by side in bed in their nightgowns with a hammer on the floor nearby. It had been, Christine said, an act of self-defense:

I’d rather have had our bosses’ hides than for them to have had ours.2

I don’t think I’d be the only person to suggest that co-ordinated eye gouging sounds an unlikely part of an unpremeditated act of self-defense, and the jury at the Papin sisters’ trial agreed.

After four minutes of deliberation, two guilty verdicts were returned. Christine was sentenced to execution by guillotine in the main square in Le Mans. Léa, the younger sister, was sentenced to ten years hard labor. Medical professionals described…

…the extraordinary moral duo formed by the two sisters, in which the younger one’s personality was absolutely annihilated by the older one’s3

and declared that…

The Papin sisters give every appearance of having an abnormal relationship, that of lovers. They never went out. Neither was known to have any emotional adventures. When they were separated in prison, Christine showed the most despair. A lover forcibly removed from his beloved mistress would not have shown greater signs of grief.4

There’s really nothing redeeming about this whole sorry tale. When the sisters were arrested and separated both refused to eat or drink for a week. In the 6 months between their arrest and trial, Christine had to be put in a straitjacket to keep her from tearing her own eyes out. When they were allowed to see each other she took off her blouse, baring her chest and crying ‘tell me yes, tell me yes.’ Christine collapsed when she was sentenced to death and refused to appeal, although her sentence was in fact commuted to hard labor for life by then French President Albert Lebrun, in January 1934. The last time they were brought face to face Christine claimed not to recognize Léa, saying ‘she is very nice, but she’s not my sister.’ She died in an asylum from self-inflicted malnutrition in May 1937. Léa’s fate is less certain. She seems to have served her time and then lived quietly with her mother.

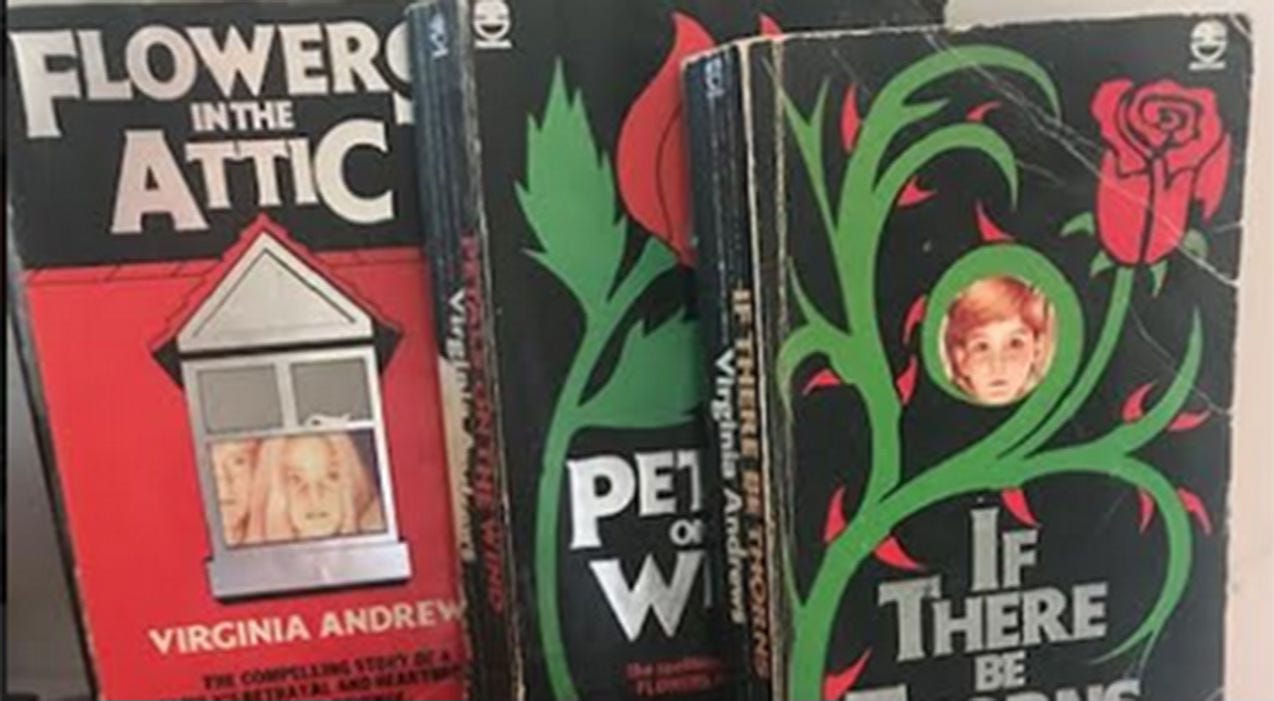

Take a little time on the internet and you’ll find plenty of articles and YouTube videos about the Papin sisters. The case is striking, horrifying even, and much has been written about the class divide here, about potential abuse from the Lancelin family, and about the sisters’ fractured relationship with their parents, particularly their mother. What it all put me in mind of most forcibly, however, was the Virginia Andrews series that began with Flowers in the Attic.

Did you read this series? Back in eighties when I was a teen, EVERYONE read it. It was shocking and fabulous and an absolute must-read story. I took a quick refresher on the story via wikipedia here, and it’s a catalogue of horror so awful that I wonder now how I stomached it. Child abuse, imprisonment, rape, incest, poisoning… this makes the Papin sisters in their little attic in Le Mans look like amateurs. All of which got me wondering about reading and why so many people seem so keen to try to ban books these days. Did Flowers in the Attic turn millions of teenage girls on to the joys of committing incest. No it did not.

What it perhaps did do, was tell millions of teenage girls that the world was not always an easy place, that parents don’t always love their children and treat them well, and that loneliness and deprivation can make nice people do strange things. How much better to learn these truths through fiction than by painful personal experience? Instead of trying to protect children from the realities of the world we live in by denying stories, why not educate them, prepare them, let them know there are different ways of living and being?

The Papin Sisters, Rachel Edwards, Oxford University Press, 2001.

ibid

ibid

ibid