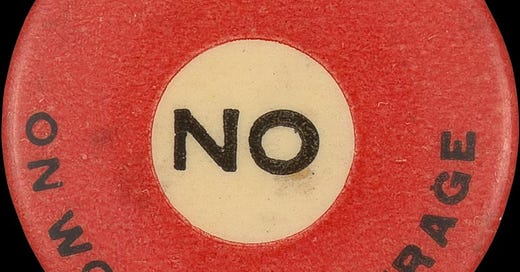

I’m not going to lie. Until I started reading about the Nathan sisters, Maud and Annie, I had no idea that there was such a thing as an anti-suffrage movement. That’s right, a whole counter movement, with women arguing against extending the vote to women in America. Turns out there was a similar thing happening in the U.K., but more on that another day perhaps. For now, I’m here to introduce you to two high-achieving sisters with a whole lot in common, but who were far from best friends, and who took up the struggle for the right to vote, on opposing sides.

Elder sister, Maud, was born in October 1862 and Annie four and a half years later, in February 1867. Their early years were spent in New York, in and around Fifth Avenue, enjoying, along with their two brothers, a comfortable life as well-to-do Sephardic Jews. The Nathans were proudly able to trace their lineage in America back to a small band of Jewish people who landed in New Amsterdam only thirty-four years after the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower.1

Although tragedy struck the family (more on that in a minute), both women became successful and influential in their chosen spheres. Maud was a protégé of Josephine Shaw Lowell, who she succeeded as president of the New York Consumers’ League. She was a high profile advocate for working women and for suffrage, becoming an acclaimed speaker who traveled extensively in America and overseas, in support of women’s right to vote. Annie, on the other hand, is now most famous for her role in founding Barnard College as a women-only university on equal footing with Columbia, but she was also a novelist, playwright, and prolific letter writer. As Susan Ware notes in her excellent book, Why They Marched, Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, both women were so busy they each maintained a clipping-service and kept scrapbooks of all their speeches, letters and engagements.2

So how did they end up on opposing sides of the suffrage question? For Susan Ware, sisterly antagonism was at the heart of the matter:

Never especially close to her older sister, and nursing simmering resentments since their mother’s death, Annie apparently relished the chance for a public feud. A lifelong gadfly, she could accomplish two goals at once: goad her older sister and make trenchant comments about women’s status designed to keep herself in the public eye.3

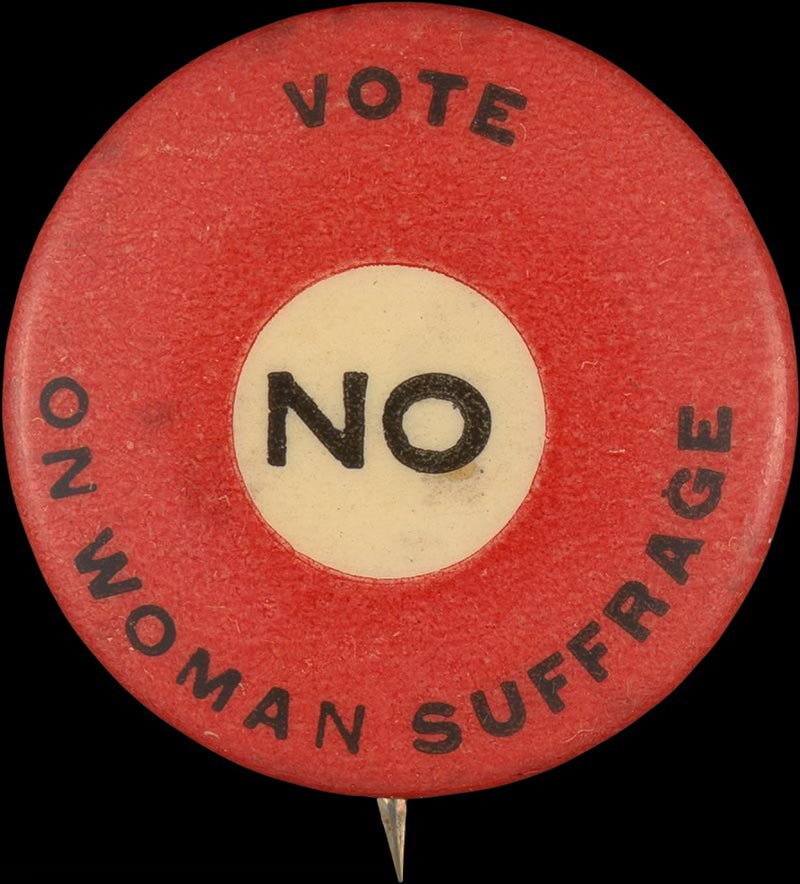

Is it just me, or does Susan Ware seem a tad critical of Annie here? “Gadfly” feels kind of harsh. So let’s try Maud’s take on her sister’s choice - from Maud’s 1933 autobiography, Once Upon a Time and Today:

My sister, Annie Nathan Meyer, who had been instrumental in founding Barnard College, for the higher education of women, who had gone to Denver, Colorado, to attend a convention of the Association for the Advancement of Women, who had addressed the Parliament of Religions in Chicago, who was one of the first women in New York to ride a bicycle - at a time when it was considered most unwomanly to make herself so conspicuous - who, in brief, stood for everything that claimed to be progressive, took her stand on the opposite side and joined the anti-suffragists!4

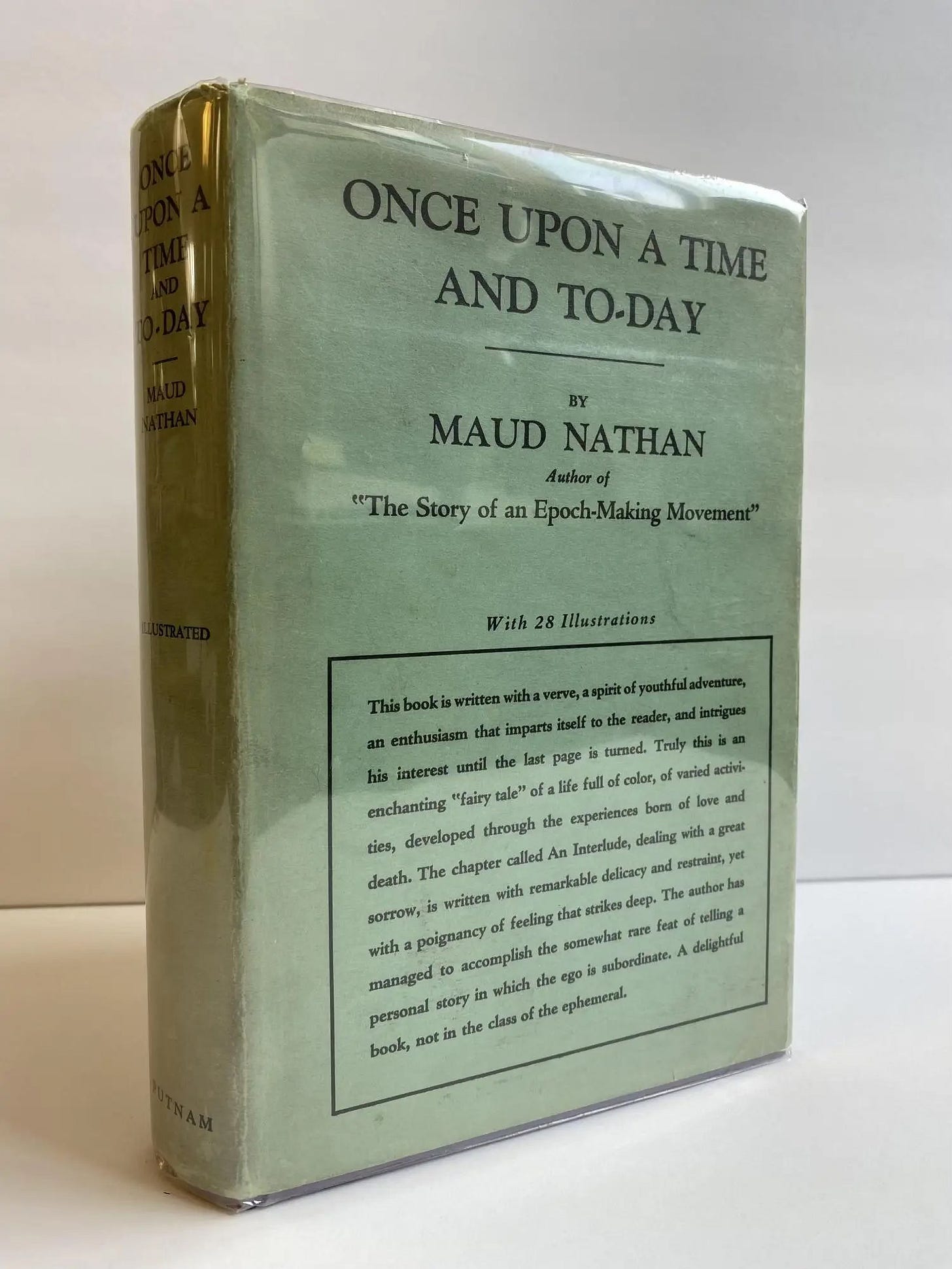

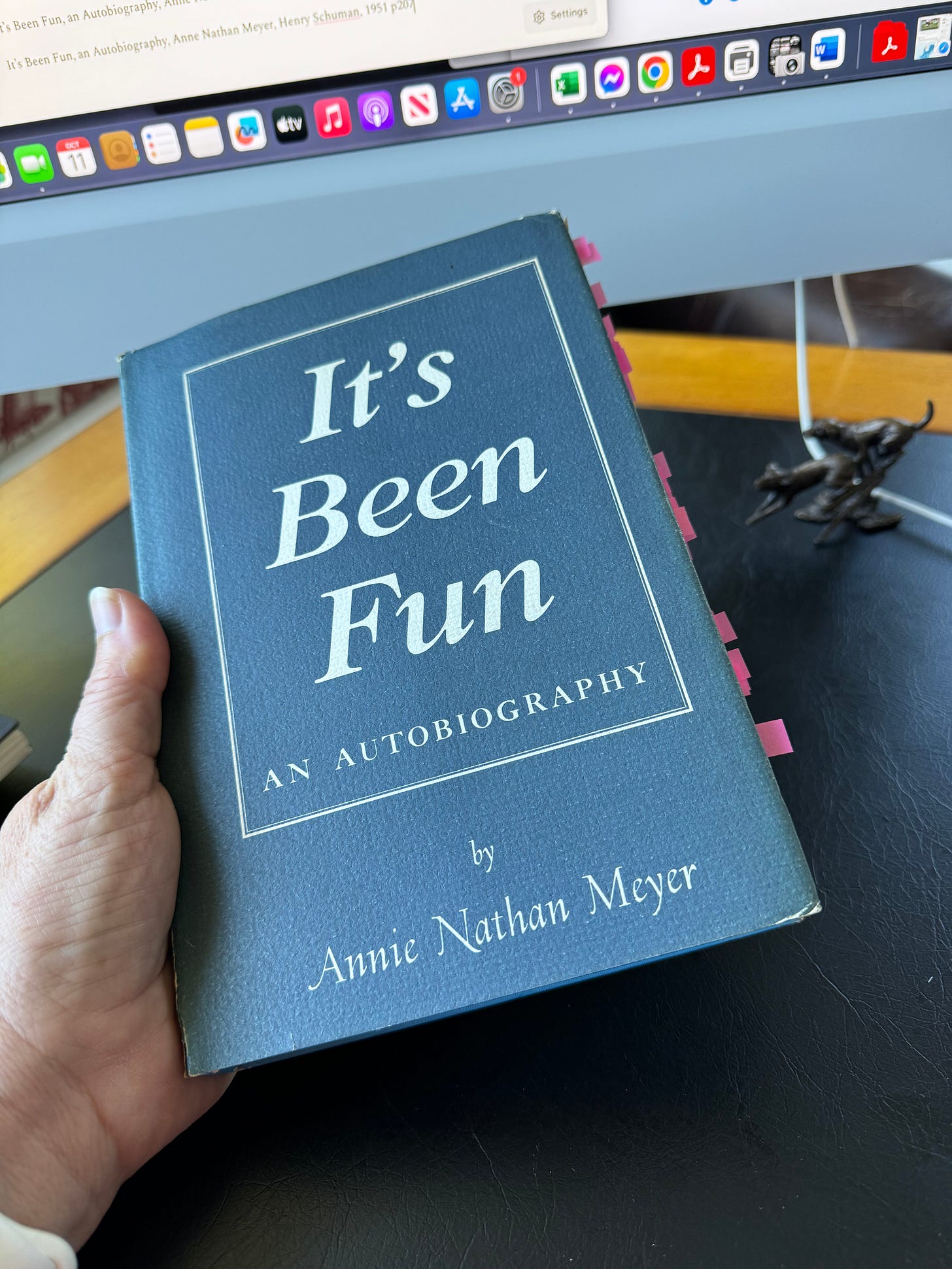

Maud’s astonishment seems genuine, so I was interested to see how Annie explained her decision in her autobiography, It’s Been Fun, written not long before her death in 1951. Here she is:

Perhaps it seems odd that one who fought so hard for higher education for women should have been against giving them the vote. Many people today forget that there were women Anti-suffragists, but I gave up many years of my life to fighting against women’s suffrage… Probably the simplest way to treat it is to explain that I was disgusted by the fantastical claims that were made as to the results that were certain to happen… That, and also a distinct flavor of sex hatred (which was always denied, but which nevertheless I always encountered), made the suffragists unsympathetic to me.5

The suffrage movement, in Annie’s view, was over-promising change. Claims women voters would end prostitution, crimes against children, political corruption, drunkenness, and even war, were nonsensical. Women would not be a voting monolith. In a comment that feels pertinent today, she wrote:

I was correct in my conviction that women would never vote as a sex. They vote - as they should - as individuals, swayed by all sorts of varying influences. Notwithstanding the excellent work of the indefatigable League of Women Voters, they have failed to vote together even when their interests as a group were clearly involved.6

This NYT article, The Women Who Fought Against the Vote, gives useful context to the suffrage/anti-suffrage argument, and references ‘the fighting Nathan sisters’, a quote that also crops up in Susan Ware’s book. I can’t find a source for that phrase, but reading both Nathan sisters’ autobiographies, there are certainly grounds for arguing that Annie’s real reason for being an anti, was because her older sister was so busy on the other side of things.

In Once Upon a Time and Today, Maud Nathan barely mentions her sister at all. Beyond the quote I’ve already given, Annie hardly gets a look in. The sisters had two brothers, and the children paired up boy/girl, boy/girl, with Maud closest to older brother Rob, and Annie with younger brother Harry. Then there’s the matter of the family tragedy. After some business failures, Maud and Annie’s family relocated from New York City to Green Bay. Maud describes their four years there as pivotal in developing her beliefs about equality, fairness and women’s rights. Away from the strictures of society life, she enjoyed much freedom - including co-educational schooling where she relished competing academically against the boys. But when Maud was sixteen, they relocated again to Chicago and their mother fell ill. She was committed to a private hospital and Maud had the task of taking her two younger siblings back to New York to live with their grandfather. Soon after came the news that their mother had died. Maud was comforted in a large part by her first cousin, Fred Nathan, with whom, despite an age gap of nineteen years and some reservations about their being cousins, she fell in love. A year later they were married and off on an eighteen month honeymoon to Europe.

Maud doesn’t figure much in Annie’s book, It’s Been Fun, either, although very early on Annie quotes Maud in Once Upon a Time and Today (talking about their heritage) so we can be sure that the younger sister did read the elder’s work. But when it comes to their childhood, Annie tells a markedly different story. In Green Bay, Annie had less freedom than Maud, being home-schooled by their mother and witnessing her mother’s illness. While Maud glosses over things, Annie describes her father’s extra-marital affairs, and her mother’s depression, nervousness and insomnia. These problems increased when they moved to Chicago when Annie was twelve. She relates how she had to call on her aunt to stop her mother trying to buy chloral, and hearing her older brother and sister discussing finding a pistol among their mother’s things.7 While neither sister states it directly, it seems their mother committed suicide. Here’s Annie on the different way the sisters were treated after of losing their mother:

I watched my sister fall gracefully on the bed where weeping relatives would promptly bend over her with advice, sympathy, and smelling salts… Gifts of all kinds, flowers, candies, tempting tidbits for her failing appetite, were showered upon my sister who showed her affection for her dead mother so prettily, so unlike the younger dry-eyed daughter who was so strangely sullen and unresponsive…The seeds of jealousy were planted then and there - a jealousy of my sister which was largely responsible for spoiling our relations for many years. It was a jealousy all the more bitter because I knew I was Mama’s favorite.8

From Maud’s marriage onwards, the sisters seem to have had little to do with or say about each other, despite having much in common. Both were clever, determined, confident, and ambitious. Both were proud of their religion and lineage, celebrating their connections to the poet, Emma Lazarus. Both were big fans of Theodore Roosevelt, each detailing their cozy relationship with the 26th President. Both lived in New York City and married significantly older men. Both marriages were long-lived and happy. Each sister had one child, although Maud’s daughter sadly passed away when she was only eight years old. This loss was a driver in Maud’s future endeavors as she sought to fill the void with championing causes and driving change. Her autobiography is full of anecdotes and name-dropping, and she reels off numerous positions she took up on boards of diverse charities, clubs and societies. She’s also not afraid to blow her own trumpet including claiming it was one of her speeches that converted President Woodrow Wilson to the women’s suffrage cause.9

Annie, in contrast, is much more forthcoming about their early years. In addition to the revelations about their mother, she tells the story of their uncle’s murder at the hands of one of their cousins. That the murdered man was the father of her sister’s husband, and the murderer, Maud’s brother-in-law, makes it all the more interesting… because Maud never mentions this upheaval in her autobiography at all. It’s in what’s said - and what isn’t - that the differences in their characters become clear.

In the last couple of weeks I’ve pored over the their autobiographies looking for evidence that sisterly antagonism was at the root of Annie’s anti-suffrage stance. She talks about receiving two requests for support on the same day - one from the pro-suffrage campaign, and one from the antis, and choosing the latter - which does give the impression that it was something of a coin toss for her. But I’ve had to go beyond It’s Been Fun to find the strongest evidence that Annie’s animosity was personal, and about her sister. In The North American Review Vol. 178, in an article written in January 1904, entitled Women’s Assumption of Sex Superiority, it’s hard not to feel the following was a direct dig at Maud:

I think there is a grave danger to the moral force of womanhood in woman's increasing participation in organized effort, in public life. To say nothing of the wire-pulling, of the unscrupulousness in attaining an end, of the unfairness, of the love of office, of the insincerity which reveal themselves in the large organizations of women, with discouraging and startling resemblance to the methods of their weaker brethren, I hold that there is certain to come a deterioration which I like to name "Platform Virtue." One who feeds on applause learns how easily it is gained, grows impatient of any task which does not win it, is apt to scorn such work as is not in the public eye… the platform habit, the club habit, the President and Secretary habit have entailed upon our women serious losses. The daily uncomplaining attention to household details that make for comfort and a restful home atmosphere; the tender, unseen care given to the children; the brooding over, watching and painstaking upbuilding of character; the brave, inspiring encouragement of the wearied wage-earner - for these things has not taste been lost?10

Ouch! Women in groups will behave badly. Women will get big-headed. Women will forget to look after their housewifely duties! And if that’s not enough, she wasn’t done with “Platform virtue,” writing:

I have hope for the future, because I know there are many strong women working quietly for this end…They are seldom found on a platform. They are not presidents of clubs. They are not be-badged "chairmen" of committees; they do not belong to Mothers' Congresses, but they are accomplishing their end in a sincere, an unspectacular, the only lasting way, through the weight of personal character, the effect of personal example, through the divine influence that is so dangerously slipping away from this organization-worshipping, this number-idolizing, world of ours11

As I’ve said, Maud barely mentions her sister in Once Upon a Time and Today. But here’s something worth considering in the light of Annie’s words above:

Men were not the only scoffers. There were women, too, who thought that these civic duties would take up too much of a housekeeper’s time. Some of the members of my family circle expressed this fear. Therefore, as a rebuke to such half-formulated criticism, I was more diligent that ever in carrying out my household duties. During preserving and pickling season, the usual allotment of jars were placed on the shelves, nor were social duties ignored. Dinner calls had to be made, afternoon teas attended, whether graft or corruption were to be exposed in city departments or not.12

There’s no doubt if I was writing a novel about the Nathan sisters this would be evidence enough for me to have a full-blown rivalry underway. I’d aim for a meeting of minds in the end, of course, although in their own reflections there are no scenes of reconciliation. In the absence of evidence, I think I’ll imagine the sisters coming together over the death of Annie’s daughter, who passed away aged twenty-eight, only three months after her wedding. This sad event happened around 1923. By then the battle for suffrage in America had been won, the Nineteenth Amendment was in place, and perhaps, I like to think, the fighting Nathan sisters were able to put down their sparring pens, and feel like family.

For more on the anti-suffrage movement in the US, there’s a good article here. And for another take on the Nathan sisters, check out this article from Barnard College.

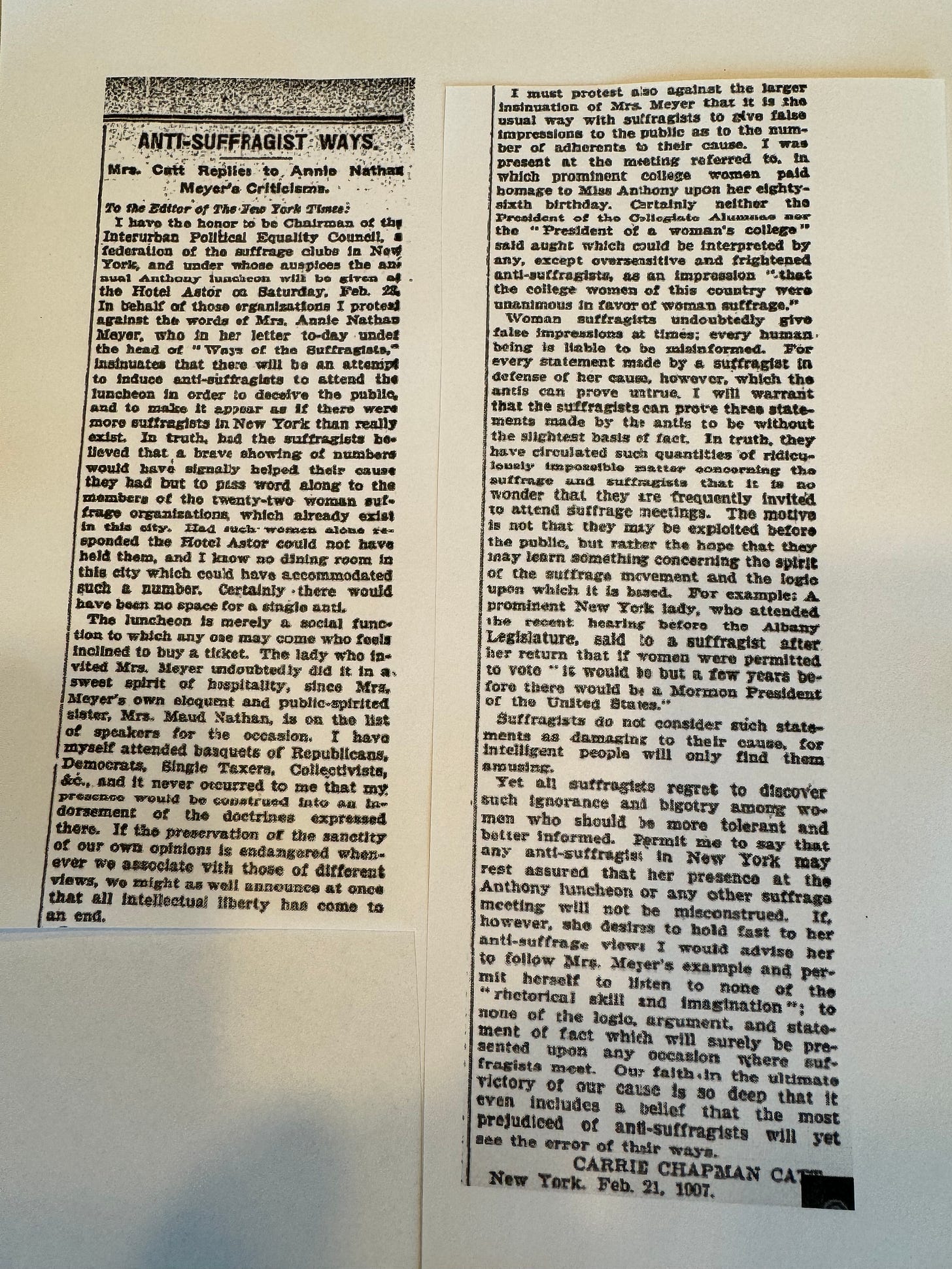

And for my politically-minded readers, here’s one last thing. I came across this letter to the New York Times, written in 1907 by leading suffragist, Carrie Chapman Catt, in response to a letter published the day before, by Annie Nathan Meyer. It’s worth a read.

Looks like fake news and arguments about crowd size were as much a part of politics as they are today!

It’s Been Fun, an Autobiography, Anne Nathan Meyer, Henry Schuman, 1951

Why They Marched, Susan Ware, Harvard University Press, 2020

Why They Marched, Susan Ware, Harvard University Press, 2020

Once Upon a Time and Today, Maud Nathan, Putnam, 1933

It’s Been Fun, an Autobiography, Anne Nathan Meyer, Henry Schuman, 1951 p202/3

It’s Been Fun, an Autobiography, Anne Nathan Meyer, Henry Schuman, 1951 p207

It’s Been Fun, an Autobiography, Anne Nathan Meyer, Henry Schuman, 1951 p115

It’s Been Fun, an Autobiography, Anne Nathan Meyer, Henry Schuman, 1951 p115

Once Upon a Time and Today, Maud Nathan, Putnam, 1933 p189

Women’s Assumption of Sex Superiority, The North American Review, Vol. 178, Jan, 1904 via JSTOR

Women’s Assumption of Sex Superiority, The North American Review, Vol. 178, Jan, 1904 via JSTOR

Once Upon a Time and Today, Maud Nathan, Putnam, 1933 p107

Another thought-provoking piece.

I can sympathize with Annie's critical eye and desire to take the devil's advocate position. Keeping a movement between the ditches is TOUGH, and sometimes it seems the best way to do it is to fight against when you think it's too far gone. I wonder if Annie was truly against the right for women to vote, or just thought, "not like this."